5 Pin M12 Socket Connector - m12 5 pin cable

Magnification can also be written in decimal format. For example, 1:2 magnification could be written as 0.5x magnification (which is found simply by doing 1 ÷ 2). This is how magnification generally appears in a list of a lens’s specifications – 0.3x, 0.14x, 0.22x, and so on. Check out this table to see some examples of lenses and their magnifications:

Spencer, you say about close-up filters: “They don’t always have the highest optical quality, so it’s not my top recommendation.” I wonder if you have any experience with Raynox DCR-250. I’m quite happy with its image quality when coupled with my telephoto lens (Nikon AF-P Nikkor 70-300mm f/4.5-5.6E ED VR). Also, unlike some other macro techniques, it gives me the flexibility to change the magnification ratio by zooming in and out with the lens.

On top of that, because high magnifications have such a low depth of field, you’ll also need to be shooting at small aperture settings when you focus especially close. This means you’re in for some photos that are dark and blurry – not to mention out of focus, since focusing is also difficult when your depth of field may be just a few millimeters across!

The best way to get high magnifications is still to use a macro lens, but hopefully this list gave you some good ideas on how to go beyond that. Personally, my favorite of these methods is to use a set of extension tubes combined with a 35mm or 50mm prime.

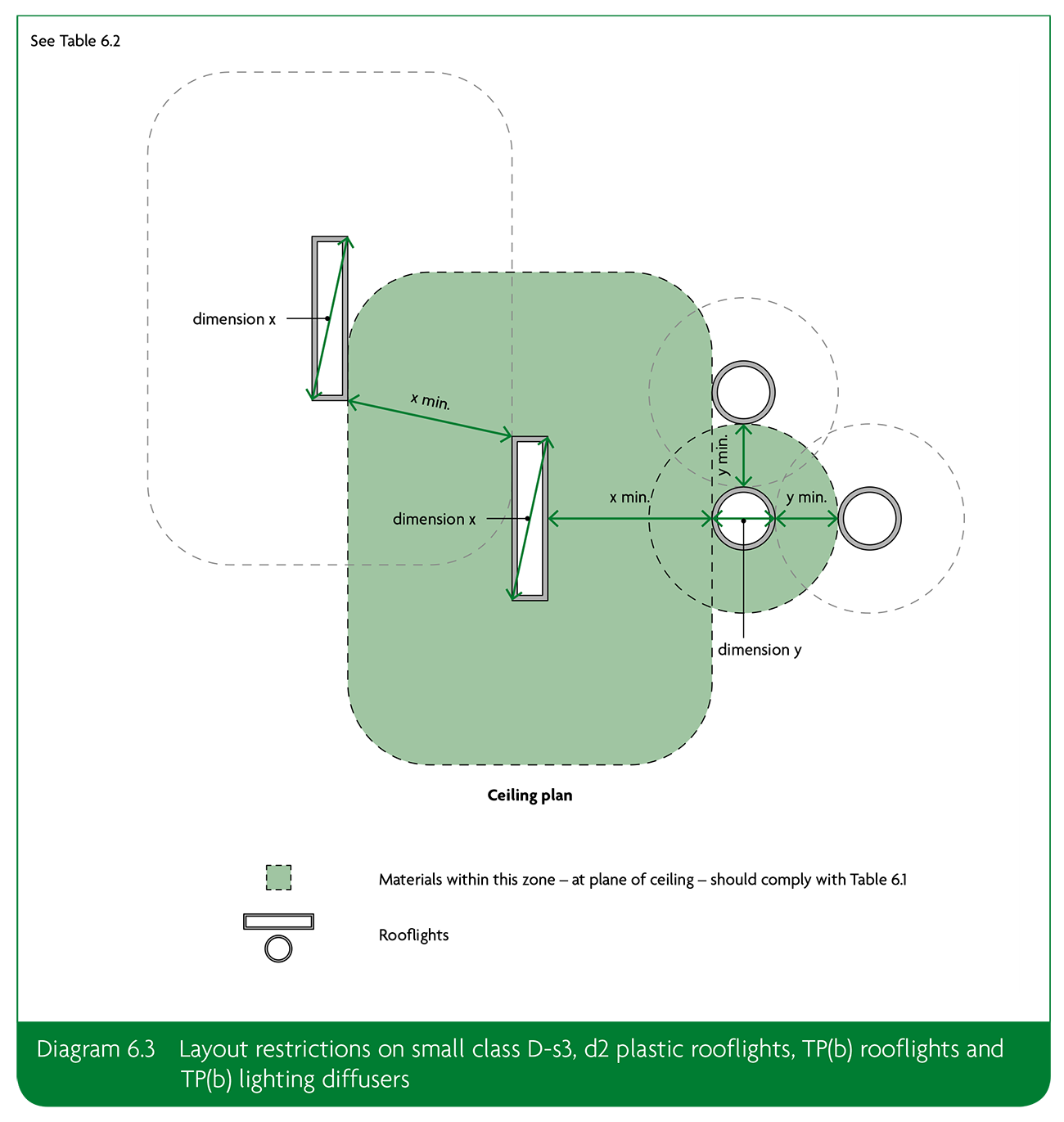

TP(a)/TP(b) relates to the rating of the material from which a lighting diffuser, when it is part of the ceiling, must be made. It is important in “buildings other than dwellings” and its purpose is to restrict the spread of fire horizontally across a ceiling.

Many long zooms like my Canon 100-400II have IQ compromises when used near MFD and there are few long primes with high magnification, good closeup image quality and modest weight and cost. Most recent lenses are either very bright, heavy and expensive primes with relatively long MFD or dim, optically compromised (for closeups) zooms; some exceptions though like Nikon PF lenses.

Unlike some camera settings like shutter speed or aperture, you don’t really need to be thinking constantly about your magnification if you want to get high quality photos. But that doesn’t mean it’s unimportant.

The first one is straightforward. Now that you understand magnification, you can easily figure out whether a particular lens offers enough close focus capabilities for your needs. For example, you may realize that you need a 1:1 macro lens for what you’re photographing, and a lens that advertises itself as macro but only reaches 1:2 won’t be enough.

You can download a complete copy of Approved Document B2 Fire and Safety. (Note that it is described as “for use in England”, but the technical guidance it contains is for the whole of the UK.)

Nice article Spencer. I particularly had an “aha!” moment when reading that magnification is a property of the lens’ projection, not the size of the sensor behind it.

In surface mounted and suspended light fittings, which are by definition not part of the ceiling, the type of material that may be used for the diffuser is regulated by the appropriate product standard, in this case BS EN60598. Note that this is a product standard, not a building standard, and 60598 makes no mention of TP(a) or TP(b) at all.

If you know what magnification you’re at, you’ll have a good idea of the depth of field you can get. For example, I know that when I’m at 1:1 magnification, I need to use an aperture of at least f/16 in order to get enough depth of field, and maybe even f/22. By focusing a bit farther back – say, 1:2 magnification – it becomes possible to use f/8 or f/11 instead, for the same depth of field.

The advantage therefore in using light fittings with TP(a) rated diffusers is that no checks or calculations are required to ensure that their usage is within the stipulations of the building regulations.

The only way to increase magnification without resorting to external accessories is to focus closer and closer (or buy a different lens).

That said, if you’re not at your lens’s maximum magnification (nor very close to it), large camera sensors still have the same benefits as always.

Excellent article! So when compare a 70-200mm f2.8 lens at 100mm and a macro 100mm f2.8 lens, one has to compare at the each’s minimum distance, The 70-200mm f2.8 has min. focus distance at 70cm and the macro has the min distance at 26cm (my case). If you compare both at 70cm in distance from the subject, then the results (depth of field, bokeh) are same, right? But the 70-200 can never focus at 26mm. On the other hand, once move the 100mm macro to its min. at 26cmm, the depth of field is much narrower, that’s why one needs smaller aperture to increase the depth of field, and thus need better lighting. Some people suggest that bring a hand light with you. That’s also why a macro lens mostly at no brighter than f2.8 because you have to reduce it to maybe f5.6 at 26cm anyway. Am I right? I did not pay too much attention to Maximum Magnification until I read your article because I am considering buying a macro lens which is on sale (Canon RF 100mm f2.8). Again. thank you. I have learned a lot.

Diffusers made of TP(a) rated material can be used to an unlimited extent in the ceilings of rooms (offices, classrooms etc) and circulation areas (corridors, lift lobbies etc). The UK Building Regulations do not require minimum spacings between TP(a) rated diffusers nor do they limit the % of the ceiling area that can be made of TP(a) rated diffusers.

Fittings with TP(a) rated diffusers can be used in a few additional circumstances, but in the great majority of situations their use is not required and the additional expenditure and potential loss of efficiency has no cost justification.

High magnifications are a lot of fun to use, but it’s not always easy to get sharp photos once you go beyond a certain point. That’s because you’re not just magnifying your subject at these ultra-close focusing distances; you’re also magnifying things like camera shake and subject motion.

It seems to me that there is a trend to use long telelenses rather than macro lenses or adapters etc. for macro subjects like butterflies and damselflies. This has the advantage of not needing to come close with risk of disturbing the insect. There are some example pictures taken with a telelens in your article, however the magnification (that must be high) is not discussed. I’m using myself a 70-200 mm semi-macro lens at the long end, sometimes combined with an extension tube, but I wonder whether an even longer lens for flying insects would not be more useful. Extension tubes have the disadvantage of getting too close to your living subject.

Magnification, also known as reproduction ratio, is a property of a camera lens which describes how closely you’ve focused. Specifically, magnification is the ratio between an object’s size when projected on a camera sensor versus its size in the real world. Magnification is usually written as a ratio, such as 1:2, which is said aloud as “one to two magnification.”

The takeaway is that small camera sensors can actually work great for this type of high-magnification macro photography. In fact, if they have smaller pixels than the full frame camera, they’re likely to be at an advantage.

Longer lenses (especially from 400mm or so) have disadvantages too to like lower native magnification, more size/weight that makes tracking fast/erratic flying subjects more difficult. DOF can be so small that it can be impossible to find and focus on the subject before it is out of the frame again. Because of those limitations I prefer a 100-200mm lens for the fastest dragonflies. Longer lenses are nice though when the subject is hovering or gliding.

If you’re reading this article, chances are you want to find out how to get as much magnification as possible. If the tips above for getting high magnification with your existing lenses aren’t enough, it might be time to get a shiny new lens with even more magnification.

The difference between TP(a) and TP(b) rated materials is in their composition and thickness or how they react under test conditions when a flame is applied to them.

Limited restrictions apply to the use of TP(b) rated diffusers in both rooms and circulation areas, and, as with TP(a) rated diffusers, TP(b) rated diffusers cannot be used at all as part of the ceiling in a protected stairway.

Would you consider doing a similar article on viewfinder magnification? I can’t wrap my head around the magnification spec of “0.77x” (for example) of modern OVFs & EVFs.

Hopefully this article answered your questions about magnification in photography. I’ve also introduced the challenges of getting sharp photos at high magnifications, which you can learn more about in our longer macro photography guide.

I'm Spencer Cox, a landscape photographer based in Colorado. I started writing for Photography Life a decade ago, and now I run the website in collaboration with Nasim. I've used nearly every digital camera system under the sun, but for my personal work, I love the slow-paced nature of large format film. You can see more at my personal website and my not-exactly-active Instagram page.

If you do any macro or close-up photography, you’ll likely come across the term “magnification.” Even outside of macro photography, most camera lenses include their maximum magnification in the list of specs.

For instance, a 24 megapixel APS-C camera is usually preferable to a 24 megapixel full-frame camera if you need as much detail as possible on a high magnification subject. On the other hand, a 45MP full-frame camera and a 20MP APS-C camera have almost exactly the same pixel density, so neither is preferable to the other for macro.

“Fire Rated” is completely different. This refers to light fittings that are recessed into a ceiling that is itself a barrier to the spread of fire vertically from one floor in a building to the one above and which may also endanger fire and rescue personnel if it collapses quickly in the event of a fire.

At the same time, you’ll notice that a macro lens can (seemingly) capture a more magnified view of your subject when you’re using a crop sensor camera. What gives?

The other context in which magnification matters is in figuring out your depth of field. No matter what lens you have, your depth of field is going to be very shallow at high magnifications, and it falls off dramatically once you’re at 1:1 magnification and greater.

If you don’t mind using accessories to go further, here are some things you can do to get more magnification than your lens natively allows:

Thanks for an informative and, to me, unrealised aspect of focus. Does this relate to a situation were a large aperture (eg F5.6) has been used in a far ranging landscape shot, and yet (paradoxically to me) the shot is in focus from front to back? I am confused as to how this can be, because it seems to contradict the rule of smaller aperture = greater depth of field. I am sorry if this turns out to be off subject.

Polycarbonate diffusers over 3mm thick are automatically classified as TP(a), along with any other thermoplastic material that self-extinguishes within 5 seconds when a flame has been removed. TP(b) diffusers may burn, but not at a speed of more than 50mm per minute.

Marcin, that’s a good point. I was thinking back to my negative experiences with a really cheap one, but if you get a good close-up filter, you can get some high quality images. I haven’t used the Raynox, but from sample images I’m seeing online, it looks quite good. I don’t see any of the severe chromatic aberrations that plague some of the cheaper close-up filters. Using it on a zoom to get variable magnification is also a good plan.

The closer you focus, the larger your magnification will be. Macro lenses routinely go to about 1:1 magnification, although some (such as the Zeiss 100mm f/2 Macro) can only go to 1:2 magnification. A few specialty macro lenses can go beyond 1:1 magnification, such as the Laowa 100mm f/2.8, which can go to 2:1. A popular choice among macro photography enthusiasts is the Canon MP-E 65mm f/2.8, which can go all the way to 5:1 magnification! However, this lens can only shoot macro photos and cannot focus on anything distant from the lens; it’s confined to the focusing range from 1:1 to 5:1 magnification.

Most macro lenses tell you their current magnification in the same information window as your focusing distance. For example, on my Nikon 105mm f/2.8 macro, the magnification is visible in the window here:

However, if your subject is moving, or you’re shooting handheld, focus stacking is much harder, if not impossible. At that point, the best option is to use a flash while practicing your best close-up focusing technique.

In a Protected Stairway no thermoplastic materials at all (neither TP(a) nor TP(b) rated) can be used as part of the ceiling.

If it helps, you can think about it like this: Shooting with a crop sensor is like cropping an image from a full-frame sensor. In the same way that cropping a photo doesn’t increase magnification, neither does using a crop sensor. But it does make the subject larger in your final image.

On the great majority of lighting projects recessed fittings with TP(b) rated diffusers are a legitimate and responsible choice.

On one hand, magnification doesn’t change at all because of your sensor size. It doesn’t even matter if you have a sensor; magnification is a property of the lens and the lens alone.

What does change, however, is that the coin takes up a greater percentage of the smaller sensor. If you were to make a print of both of these photos and display them at the same size, obviously the coin would be larger on the photo from the aps-c sensor. So, even though the magnification hasn’t changed, the composition has.

Navek, no worries, that’s a good question. Depth of field depends on more than just your aperture. There are also two other factors: focal length and focusing distance.

Some lighting manufacturers, including NVC , offer a range of LED panels with a choice of TP(a) and TP(b) ratings. By using such manufacturers and following their advice in product selection contractors can be confident they are using the most cost-effective solution while maintaining strict compliance with the UK building regulations.

These challenges aren’t easy to overcome, but it’s possible to do it with some effort, and that’s half of what makes macro photography so fun! When you do succeed at getting a sharp photo at extremely high magnifications, it’s very rewarding.

PL provides various digital photography news, reviews, articles, tips, tutorials and guides to photographers of all levels

When a lighting diffuser, such as in a 600 x 600 LED recessed panel, is part of a ceiling it is mandatory that it must be made of TP(a) or TP(b) rated materials.

Many dragonfly / butterfly photographers use longer lenses like a 4/300mm because of longer working distance and better background blur, especially for in-flight shots. However, this is more “close-up” than real “macro” with magnifications in the 1:10 to 1:2 or so range.

On Photography Life, you already get world-class articles with no advertising every day for free. As a Member, you'll get even more:

This is because depth of field shrinks as you zoom in and focus closer. Because magnification can be thought of (and even expressed mathematically) as a combination of focal length and focusing distance, there’s no way around it: High magnifications have low depth of field.

I just found this article when trying to understand the magnification offered by a non-macro lens. This 100mm full-frame lens. The manufacturer’s (Sony’s) blurb, complete with their colorful verbiage says: “Because one of the main features of this lens is bokeh, it has been provided with a macro ring switch that extends the lens’s range into the macro region where bokeh can be used to great effect. The macro mode provides 1.87 ft (0.57 m) minimum focus with 0.25x maximum magnification, with no compromise in resolution performance.” It is that ” 0.25x maximum magnification” I am trying to understand. I’ve got a pretty good reference for what 1:1 would be, as full frame based on the old 35mm film would be the size of a 35mm slide. I can picture four such rectangles forming a larger rectangle, (2×2)) or a total size 4x any one slide’s image. 4x sure sounds like 25%, but I am unsure that is the correct view. For all I know that 25% might be applied linearly, meaning I need to picture a 4×4 rectangle that covers 16 times the area of the sensor (or a slide image).

Glad you found it useful, Brian! I would need to read up on the technical background behind those specifications before writing an article, but I would consider it if there’s interest. I know what you’re referring to, but I’ve only ever used that specification when comparing how large the viewfinder will seem, among cameras with the same sensor size.

A lighting diffuser is only judged to be part of the ceiling if it is recessed into it. The diagram here is taken from the UK building regulations and makes it very clear – if a light fitting is surface mounted or suspended then it is not part of the ceiling, so the consideration of TP(a) or TP(b) simply does not apply.

Alternatively, some lenses may not advertise themselves as macro lenses, even if they have pretty impressive close focusing capabilities. For example, the humble Nikon 18-55mm AF-P kit lens can reach to about 1:2.6 magnification (0.38x), and the Canon 24-70mm f/4 goes even further to 1:1.4 magnification (0.71x). That’s more than you’d get with many so-called “macro” lenses from other manufacturers! With either of these lenses, you could take close-up photos of larger subjects like flowers, lizards, dragonflies, and so on, without spending hundreds of dollars on a dedicated macro lens.

A fire-rated downlight could, in theory, include TP(b) rated materials, and an LED panel with a TP(a) rated diffuser will almost certainly not be “Fire Rated”.

This is helpful knowledge to have on the fly if you don’t have time to chimp. It’s also nice to know beforehand how to deal with certain magnifications – such as using a flash at 1:1 because of those small apertures, or using focus stacking if you get to extreme magnifications like 4:1 or 5:1 to get back depth of field.

Luckily, every manufacturer has at least one dedicated macro lens, which you can get from B&H photo with the following links:

TP(a) and TP(b) are terms used in the UK Building Regulations (UK Building Regulations, Fire Safety, Approved Document B, Volume 2 – Buildings other than dwellings) that classify lighting diffusers according to their flammability. TP means thermoplastic, and TP materials, such as polycarbonate (PC), acrylic (PMMA) and polystyrene (PS), are commonly used as diffusers in light fittings. In the UK Building Regulations these are classified as TP(a) or TP(b) and when a lighting diffuser is deemed to be part of a ceiling it must be made of either TP(a) or TP(b) rated material. No other thermoplastic material may be used.

As you can see, the coin’s projection is physically the same size on both sensors. (If it looks larger to you on the aps-c sensor, that’s just an optical illusion; the pixel dimensions are the same.) So, it doesn’t matter what size sensor I put behind the lens – it can’t change the physical size of the projection. The magnification is identical in both cases.

However, it is nearly 200 pages long, so here’s a quick summary of TP(a) and TP(b) and how these terms relate to lighting in buildings other than dwellings.

The other factor, focal length, works the same way. The further you zoom in, the less depth of field you’ll get. This is how wildlife photographers can get a shallow depth of field despite focusing far away and even using narrow apertures like f/11.

A special case is when the object is the same size in the real world as its projection on your camera sensor. This is 1:1 magnification, also known as 1x or “life size” magnification. It’s important because 1:1 magnification is considered the standard for macro photography, and most macro lenses at their closest focusing distance will be at 1:1 magnification.

For example, say that you’re doing macro photography, and the object you’re photographing has a projection on your camera sensor which is 1 inch across. If the same object is 2 inches across in the real world, your magnification is 1:2. (It doesn’t matter what units of measurement you use; the important thing is the ratio between the object’s size on your camera sensor compared to its size in the real world.)

Excellent writing. Very easy to understand for almost everybody who has taken his hands on an interchangeable lens camera. It’s concise, and nice to read, thanks.

If your subject is staying still, you can fix most of these issues by focus stacking from a tripod. Even if you don’t focus stack, simply using a tripod allows you to use longer exposures to negate the darkness of f/16 or f/22. It also makes focusing much easier.

A Protected Stairway is, in the words of Approved Document B, “A stair that leads to a final exit to a place of safety and that is adequately enclosed with fire resisting construction. Included in the definition is any exit passageway between the foot of the stair and the final exit.”

It’s similar to the situation with extreme telephoto photography. When your goal is simply to put the maximum number of pixels on a small or distant subject, a crop sensor with a small pixel pitch works very well.

I’m not surprised that you’re seeing a lot of depth of field when you focus on something far away, even at a medium aperture like f/5.6. The farther you focus, the greater your depth of field becomes. So, you’re correct that it relates to this article, where I say that your depth of field gets very shallow at high magnifications/close focusing distances.

Maybe a diagram will clear things up. Here’s how a sample subject (a coin in this example) looks at the same magnification on two different sensor sizes:

All these lenses go to 1:1 magnification or more, and will likely provide enough magnification for almost any application.

I’ve corrected that part of the article to say “if you avoid the cheap ones, this is a good way to increase your magnification.” I think my prior wording was overly negative.

Ms.Cici

Ms.Cici

8618319014500

8618319014500